By Logan Sand, Samantha Beckerman, Catherine Cox Blair.

(NRDC, Natural Resources Defence Council)

Shared mobility is comprised of short-term transportation solutions enabling users to access various shared vehicles, bicycles, or other low-speed modes. In North America alone, shared-use mobility transcends the submarkets of car-sharing, bike-sharing, ridesharing, on-demand services, shuttle services, and other emerging industries. Shared mobility

methodologies have led to commuting options that are easier, greener, and more economical. Shared mobility programs can also link critical first and last mile connections by extending convenient and cost-effective public transportation options at strategic locations. Although, these new services and tools are flooding the transportation market, communities of color along with low-income and immigrant populations often do not have access to these new mobility solutions. This can be due to language, income, and access to technology. Transportation and funding are connected and incredibly important to developing solutions for low-income communities. However, there is a fine line in balancing public funding and subsidies sustainably without over establishing fiscal commitments. The goal of this case study is to locate and examine best practices for new mobility strategies, programs, and models benefiting vulnerable populations.

Car Sharing

Car-sharing provides on-site, on-demand access to a motorized vehicle. Car-share systems are also designed for round-trip and one-way use depending on the service provider and location. Car-shares require individuals over the age of 21 to pre-register with a credit or debit card and a valid driver’s license. Users pay an annual membership fee and a fee for the

hours rented or distance traveled. Peer-to-peer car-share systems allow private residents to rent their personal vehicles to strangers, through a round-trip mechanism. The coordinating organization facilitates the connections between drivers and car owners. Nonprofit car-share programs exist solely to support users who do not own a car. These programs serve as a tool for social and environmental change by providing an accessible and affordable transportation option for the public. However, often this model requires public subsidy, donations, or grant assistance from sponsors and partners. For-profit car-share programs—like Car2Go, Enterprise Rent-A-Car and ZipCar—currently capture a larger market share. Under this model, the objective is to meet, or exceed the bottom line for stakeholders. Generally, for-profit car-share models are more organizationally expansive and have the financial backing to be more commercially aggressive.

Facts around Cars and Carshares

- Vehicle ownership increases access to jobs and economic opportunities. A study of participants of HUD’s Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing program found that low-income families with a car were twice as likely to find a job, and four times more likely to stay employed.

-

Cars are a more time-efficient mode of transit. “Data from the 2010 Census reveals that people living in central cities with a higher proportion of transit riders experience longer commutes. And since transit riders have more cumbersome commutes, they are much more likely to be tardy or absent from work.”

-

Car-shares are more cost-effective than ownership. Low-income individuals are more heavily burdened by ownership costs, loan premiums, car insurance, repairs, and variable gas prices. Car-shares package these costs to provide a more manageable financial approach. Some families can save more than $700 a month by sharing, rather than owning, a car.

Challenges to Car-Shares

- Car-share programs, while more cost-effective than car ownership, still have costs that may be prohibitive for some populations.

- Bike-share and car-share operations attempting to extend into low-income neighborhoods experience the same funding challenge. Currently, there is no structural model for publicly funded car-shares to assist low-income neighborhoods. Short-term public subsidies are beneficial, and have provided some of the most equitable car-share programs on the market. But these public subsidies are linked to prosperous economic periods and strong political support allowing for allocation of public dollars to low-income pilot programs.

- There are still cultural stigmas around car-shares, often associated as being modes for affluent millennials with credit cards.

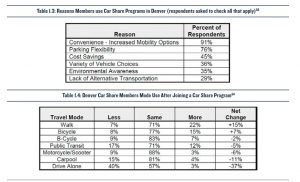

The Denver Car-share Landscape

The Denver metro region hosts a number of successful for- and non-profit model car sharing programs, including eGo Car Share, Car2Go, Zipcar, Enterprise CarShare, and Hertz Rental. The service and rates between providers varies, with round-trip, one-way, point-to-point trips charging by the minute, hour, or day. One of the oldest national car-share models,

eGo CarShare is now a Denver-based 501(c) nonprofit that strategically partners with community and transportation organizations to expand round-trip service and availability throughout the Denver metro region. eGo has a hybrid and electric fleet, and mission to limit environmental and social impacts from vehicular ownership. eGo has capitalized on members’ desire to choose a local option over “another for-profit” model. The eGo program is not a standard car-share. In 2014, eGo received CMAQ funding from the Denver Regional Council of Governments (DRCOG) to launch the Affordable Housing Multi-modal Toolkit for low-income residents in Boulder and Denver. Mile High Connects and The Denver Foundation provided additional funding. The program partners with Boulder Housing Partners (BHP), Denver Housing Authority (DHA), and Habitat for Humanity of Metro Denver (HFHMD) to provide qualified households with “significantly subsidized monthly transit passes, easy access to car-sharing at discounted rates, free or discounted B-cycle memberships and/or access to pool bikes, and education about the multi-modal transportation options available to them.”

This program concludes in 2016, and is currently working in the Mariposa and Globeville neighborhoods.

Conclusions

Shared mobility options are most effective for low-income communities when tied to mass transit. Therefore, shared mobility and mass transit systems need to complement each other. In addition, data transparency across all shared mobility programs should remain a universal priority. The first challenge is finding comparable metrics between systems that are

above the basic bike- and car-share usage statistics. Another challenge of the shared economy is reaching an authentic understanding of grassroots community needs. Equitable shared mobility options are best utilized when combined with advocacy or community-based organizations. Bike-sharing and car-sharing enhancements need to be more intentional with coordinated through advocacy groups and community-based organizations, which can identify low-income community needs and gaps with mass transit systems. In many low-income communities, a majority of ride-sharing happens on buses. As shared mobility options evolve, community-based organizations need to be part of the design and marketing engagement. Funding mechanisms and support for new mobility systems vary on many

levels. Operations that have reliable funding structures and strategies are the most successful and sustainable. Shared mobility operations are becoming more dynamic, innovative, and cost effective. However, they still need to be connected to underrepresented low-income communities across the nation. Simply, the goal of this case study is to highlight best practices in shared mobility concepts, and to identify challenges and constraints. Ultimately, as we begin to examine opportunities and address challenges in the Denver region, this study shall serve as a comprehensive reference point.

Please, read the full case study at: https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/shared-mobility-cs.pdf

Leave a Reply