Researchers at MIT say they’ve found an efficient dispatching algorithm that can cut a city’s fleet of taxis by 30 percent.

They describe their work in a paper published today in Nature.

“New York would need 30 percent fewer vehicles if the taxi fleet, even with human drivers, is managed better,” Carlo Ratti, the director of MIT’s Senseable City Lab tells IEEE Spectrum. That’s a big savings, both in taxis and in the space they take up on city streets. New York’s 14,000-odd taxis log some 500,000 trips a day.

The technology would seem to help the beleaguered taxi business fend off private ride-hailing services, like Uber and Lyft. They have their own algorithms, optimized partly to match drivers and passengers and partly to pool ride-sharing customers.

Ride sharing was the first thing Ratti and his colleagues studied, back in 2014, when they determined that if taxi passengers in Manhattan could put up with just a five-minute delay, nearly 95 percent of their trips could be shared. That would cut the total time that passengers spend in taxis by up to 40 percent.

This time, the researchers asked how a better dispatching model could make better use of the taxi fleet as it’s run today, that is, without assuming much ride sharing. They call it the minimum fleet problem, and they handle it as a master pool player does, by making each shot set up the next one. By giving due weight to minimizing the distance between a taxi’s destination and the origin of its next potential trip, the model moves more passengers per vehicle over a given period of time.

A perfect solution would lay to rest the famous Traveling Salesman Problem, which tries to find the shortest path a salesman must take to hit every spot on his route. That problem quickly becomes intractable, however, as the number of spots increases. You could solve it for Mayberry, but not for Manhattan.

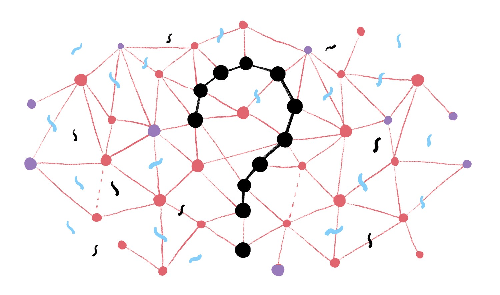

Instead, the MIT researchers created what they call a vehicle sharing network, similar to the network they used in 2014 for optimizing ride sharing. It looks like a graph in which each node represents a trip and each line linking two nodes represents a pair of trips that one vehicle can handle. Manipulating the layout of the graph provides ways of improving (if not perfecting) the solution.

What if all of Manhattan’s 280,000 or so vehicles were robocars, driving themselves while under the control of the MIT master plan? “If we were to look at a fully autonomous city,” Rotti says, “the reduction in vehicles would be closer to 50 percent.”